Deconstructing Peter May's "The Open Question" - Part 2: Factual Errors

Whoever is careless with the truth in small matters cannot be trusted with important matters.

- Albert Einstein

Page xiii - May writes about the last hole of the playoff at Olympic in 1955, where Hogan drove into thick rough:

It took him two shots just to get his ball back into the fairway...

Hogan needed three swings to escape the rough.

Page 10 - May writes:

The Masters vowed to continue in April 1942, with tournament chairman Clifford Roberts originally saying he expected 88 players.

On February 7, 1942, in the first public statement concerning the 1942 Masters invitees, Roberts announced that although 88 invitations were being sent, he expected no more than 50 attendees.1

Page 13 - May writes:

The CDGA thought Ridgemoor to be the closest course of championship caliber to the heart of the city.

May himself cites reports that Ridgemoor was not perceived as a "championship course;" from page 115:

Grantland Rice wrote, "Ridgemoor is not a championship course. It is a membership course."

May also omits, or is unaware, that after the Hale America's conclusion, Craig Wood dismissed Ridgemoor with "It's just a nice members' course,"2 while sportswriter Joe Williams called Ridgemoor "a weekend golfer's paradise...never meant for tournament players."3

Page 18 - May writes that at the 1942 Masters "Hogan and Nelson were the tournament favorites," however, on the first day of play, the Associated Press reported:

Unofficial odds made Hogan a betting favorite at 5-to-1, and bracketed Nelson, Wood and Sam Snead at 6-to-1.4

Page 19 - May writes about the 1942 Masters playoff between Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson:

This was also the last time those two ever went head-to-head in a tournament. Nelson never lost to Hogan in a playoff or match-play event, and he never lost when he went head-to-head with Sam Snead...

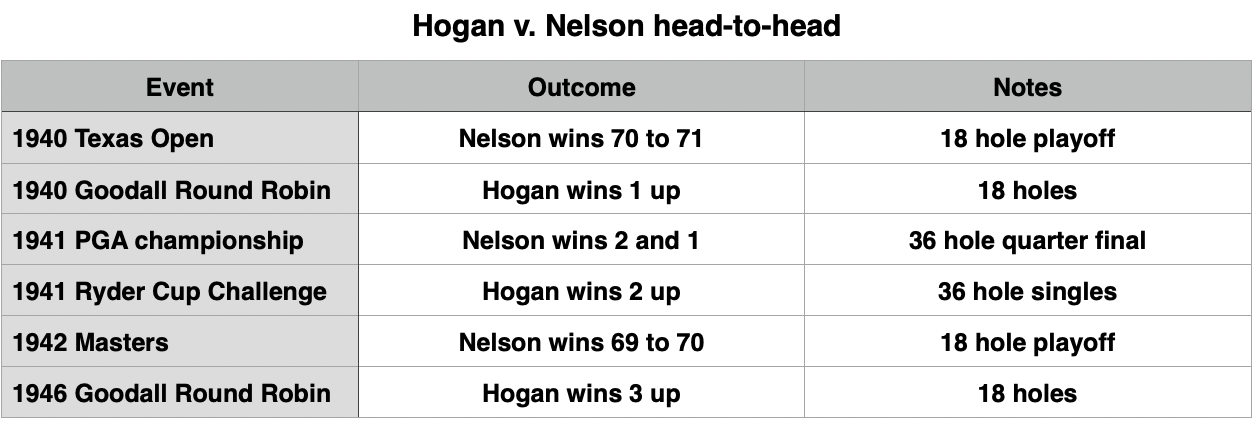

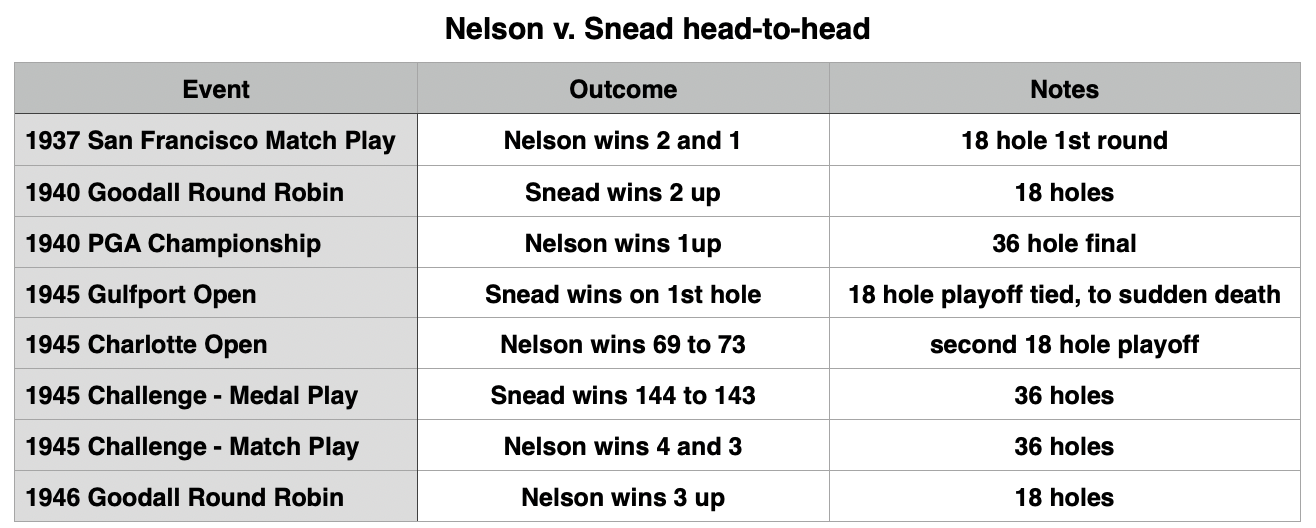

All three claims are false. Hogan and Nelson would meet one more time at the 1946 Goodall Round Robin, where Hogan would prevail. Overall, Nelson and Hogan met head-to-head six times as professionals, with each winning on three occasions:

Snead and Nelson faced off eight times, with Nelson prevailing five times, Snead three:

Page 19 - May writes:

Then again, [Nelson] didn't do too terribly in 1946, winning 5 times.

Nelson won six times in 1946.

Page 21 - May wrote:

The record number of entries had to be whittled down to a manageable 100 or so, and that is what the local and sectional qualifying tournaments are meant to accomplish.

The number of entries to be allowed into the field through qualifying was set at 80, although 82 was the actual total.

Page 29 - May writes:

As Ridgemoor Country Club was getting ready to host the biggest event in its 37-year history, an Associated Press report marveled at the preparations for the Hale America Tournament. "Ridgemoor has been lengthened and generally toughened up with bottleneck fairways and heavy thickets of trees," the report read.

The Associated Press report May cites has no credibility. The June 2nd article is by the Associated Press' Charles Chamberlain, a staff writer who appears to have been directed to write breathlessly about the imaginary challenges of Ridgemoor.4 On June 12, Chamberlain authored a wildly over-the-top assessment, shown below, hailing Ridgemoor as "one of the sternest tests of golfing concentration and accuracy in the country," where the potential winner "must possess excellent control, deadly accuracy in his long and short iron game and deep concentration--or be able to smash a niblick shot 250 yards from the sand":5 Page 33 - May writes:

Page 33 - May writes:

Ben Hogan came out of wrenching poverty and lived for a while on oranges.

"Living on oranges" was the result of poor planning, a case of self-inflicted "poverty," not because his family growing up couldn't put food on the table. During his first trip out west to play the winter tour, Hogan had to eat oranges for a few days while waiting for an additional loan from Marvin Leonard to arrive.6 Hogan would later ruefully recall he was foolish to venture on tour with inadequate funds.7

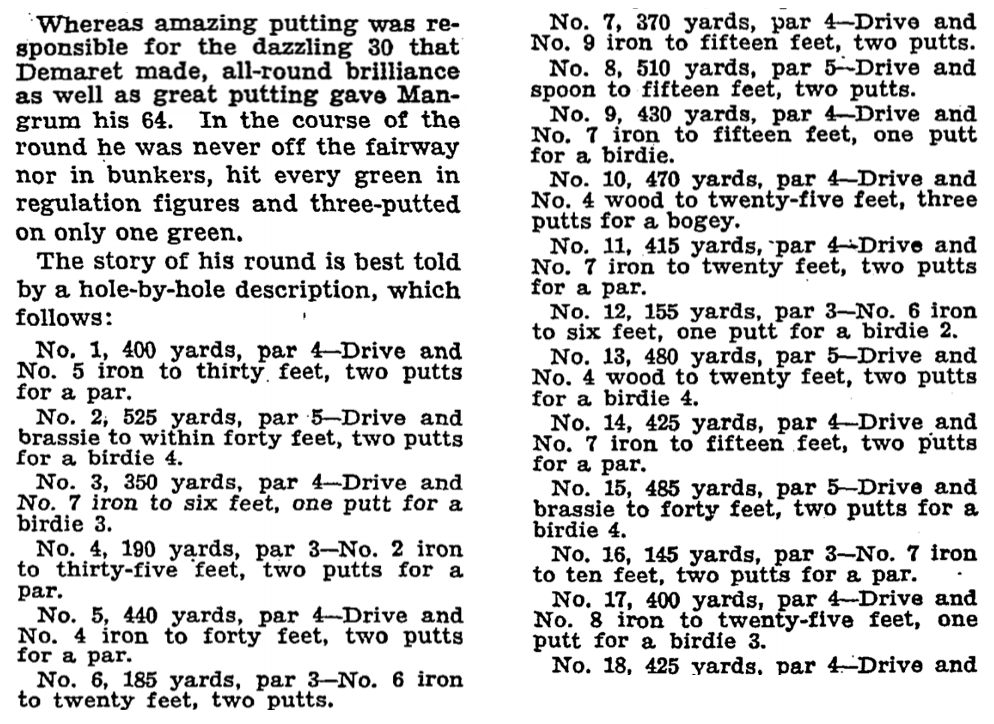

Page 38 - May writes this concerning Lloyd Mangrum's first round 64 at the 1940 Masters:

Mangrum left the grounds before reporters could get him to talk about the round, so there was no breakdown of the historic 18 from the man who achieved it on his first crack at the celebrated course.

May is mistaken: a detailed "breakdown" of Mangrum's round somehow found its way into the April 5, 1940 issue of The New York Times:8

Page 39 - May writes that coming into the Hale America "Hogan and Snead had three wins apiece." Both tallies are incorrect. Hogan actually had four wins: the LA Open, San Francisco Open, his second win at the prestigious North-South and his third consecutive win at Asheville. Although Snead had three wins, just one was official, the St. Petersburg Open.

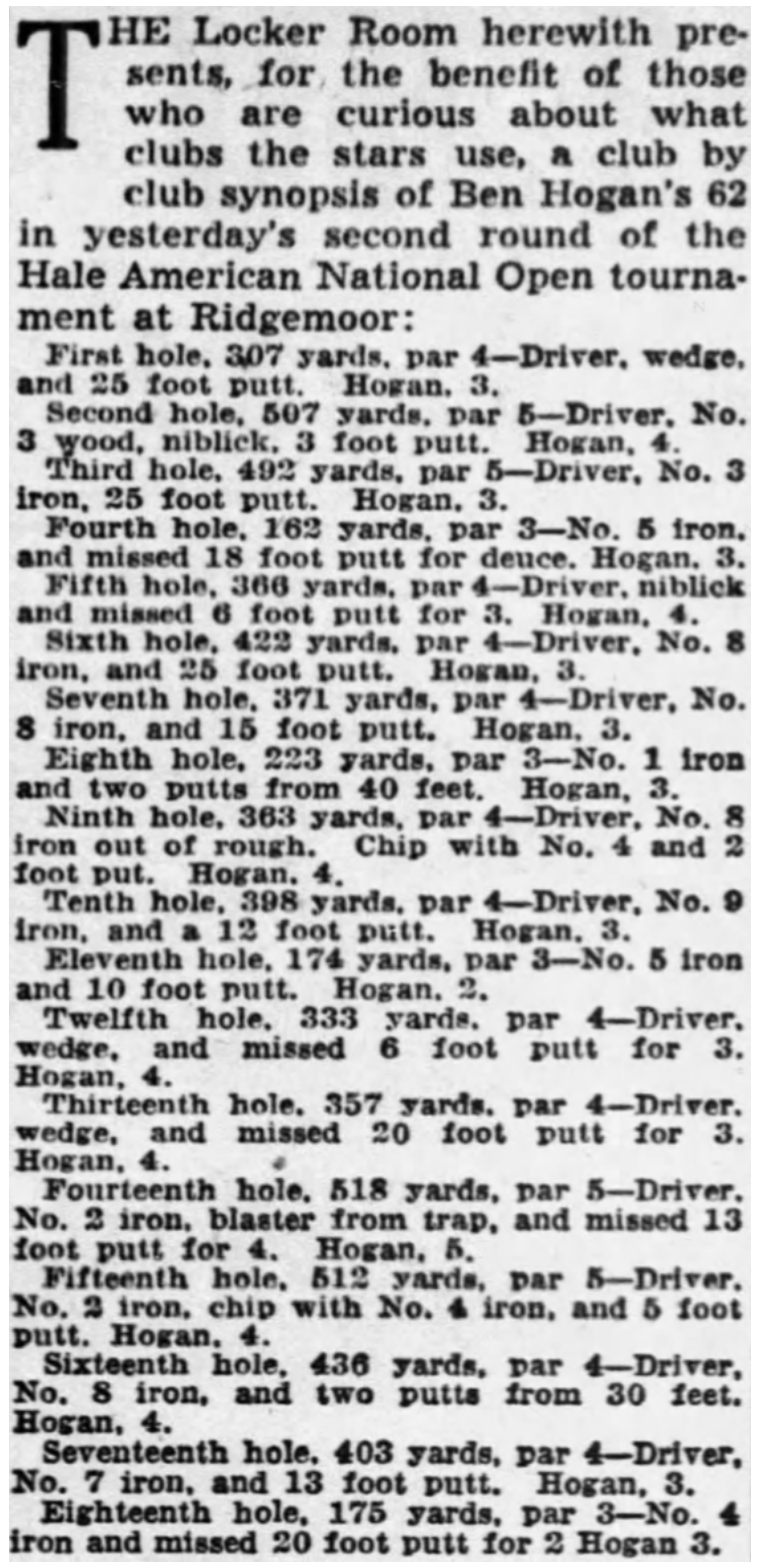

Pages 47 through 54: May devotes much of these pages to lauding Hogan's second round 62, but omits the shot-by-shot details published the next day:9

Page 48 - May recounts an anecdote meant to illustrate Hogan's "surreal tunnel vision" while playing a tournament round. The story involves Hogan and Claude Harmon while playing partners during the 1947 Masters, and alleges Hogan was so focused on his own game, he was oblivious to Harmon's ace on the 12th hole. May omits, or is simply unaware, that Hogan was merely pulling Harmon's leg, as he explained to Dr. Bob Rotella:

I knew he'd made a one. I always felt it was my obligation to watch my playing partner's ball...He knew I was teasing him, but it did make a great story.10

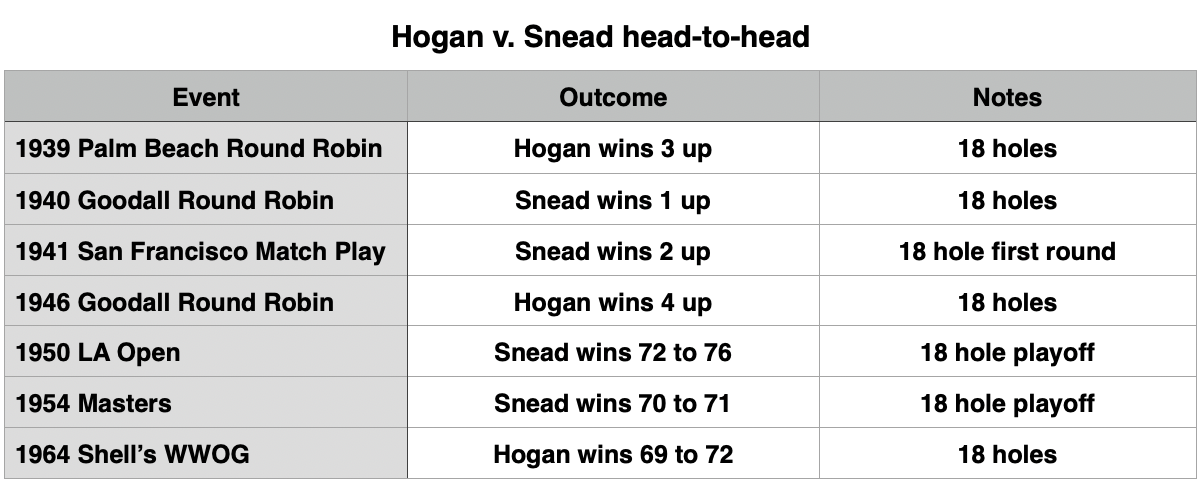

Page 49 - May writes that Sam Snead "beat Hogan in their three head-to-head matches," which is false. Sam and Ben had seven head-to-head encounters, with Sam winning four times to Ben's three:

Page 54 - May writes that Hogan played 294 tournaments from "1932 until 1970." May shortchanges Hogan's playing career as a professional by three years: Hogan turned pro on January 31, 1930, ended his playing career in 1971, and made at least 348 starts over that period when unofficial events are included.

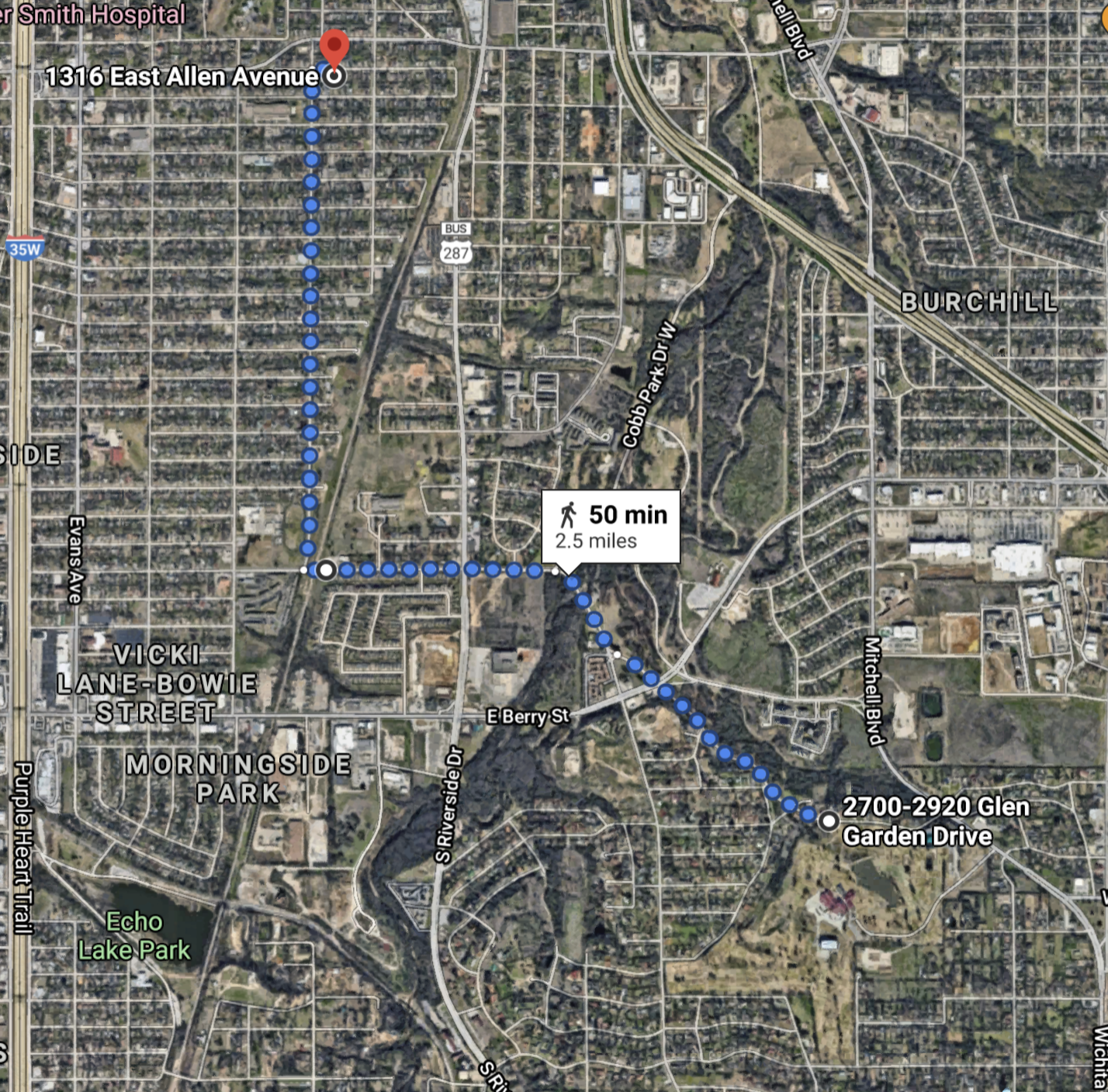

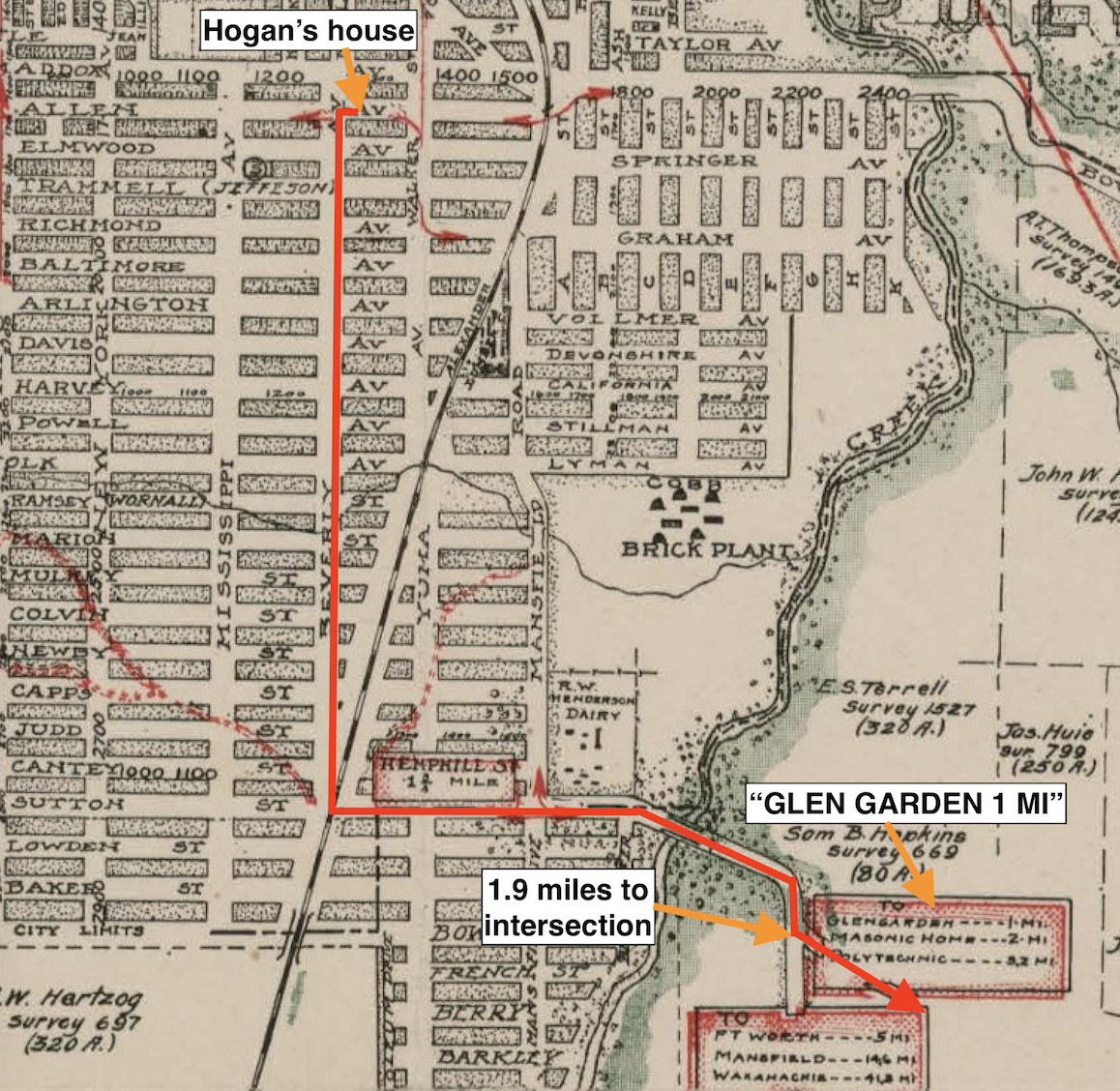

Page 55 - May writes that Hogan walked "almost seven miles from his home to the club." The actual distance is 2.5 miles to the course boundary: This map from 1919 confirms the route mapped above was available to the young Hogan in the 1920s:

This map from 1919 confirms the route mapped above was available to the young Hogan in the 1920s: Page 56 - May writes that Byron Nelson's victory in the 1927 Christmas Caddy Tournament earned him "Glen Garden's only junior membership the following year." That is a myth. Several accounts, including one by Nelson in 1937, attribute the membership to a recommendation by the club manager ("Byron Nelson is the only caddie who doesn't drink, smoke or curse"),11 and Nelson's fine play in a tournament at a local public course, Katy Lake.12

Page 56 - May writes that Byron Nelson's victory in the 1927 Christmas Caddy Tournament earned him "Glen Garden's only junior membership the following year." That is a myth. Several accounts, including one by Nelson in 1937, attribute the membership to a recommendation by the club manager ("Byron Nelson is the only caddie who doesn't drink, smoke or curse"),11 and Nelson's fine play in a tournament at a local public course, Katy Lake.12

Page 56 - May writes that for aspiring pros starting out during the Depression "fruit was a subsistence food group":

Demaret recalled a tournament in California where the players would deliberately take an out-of-bounds penalty to rummage through an adjacent orange grove and stuff their bags with oranges while supposedly trying to find their errant shots.

May fails to mention that these excursions took place during practice rounds.13

Page 57 - May writes:

In his first four years as a professional, Ben Hogan earned a total of $362 over 10 tournaments. Two of those tournaments were the US Open, where he failed to make the cut in 1934 and 1935. He fared marginally better in 1938, when he won more money in one tournament ($375 for a third-place finish at the Lake Placid Open) than he won in the previous four years combined.

May makes several errors in the above. As already noted, Hogan turned pro in 1930, not 1932. Hogan earned no money in '30 and '31 in five tour event starts. From 1932 through 1934, Hogan won $512.50 in 12 starts. Hogan did not play in any events in 1935. In 1936, Hogan played in two events, including the US Open where he missed the cut, and again cashed no checks. Hogan joined the tour full-time in July 1937 and over the remainder of the year won $1,312.92 in 12 starts, including $375 for a third place finish at Lake Placid. In 1938, Hogan won $4,829.98 in 24 starts, while skipping the Lake Placid Open that season.

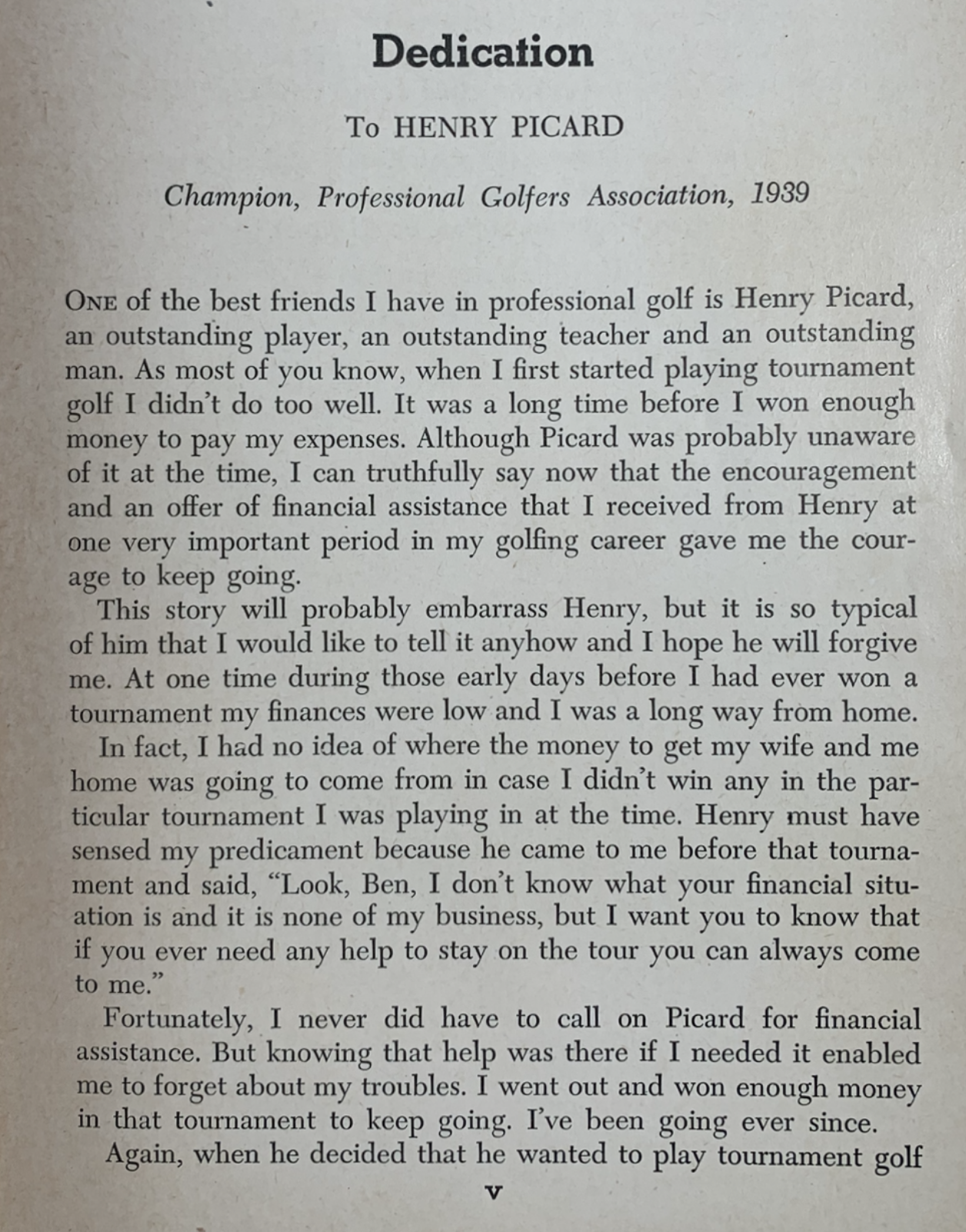

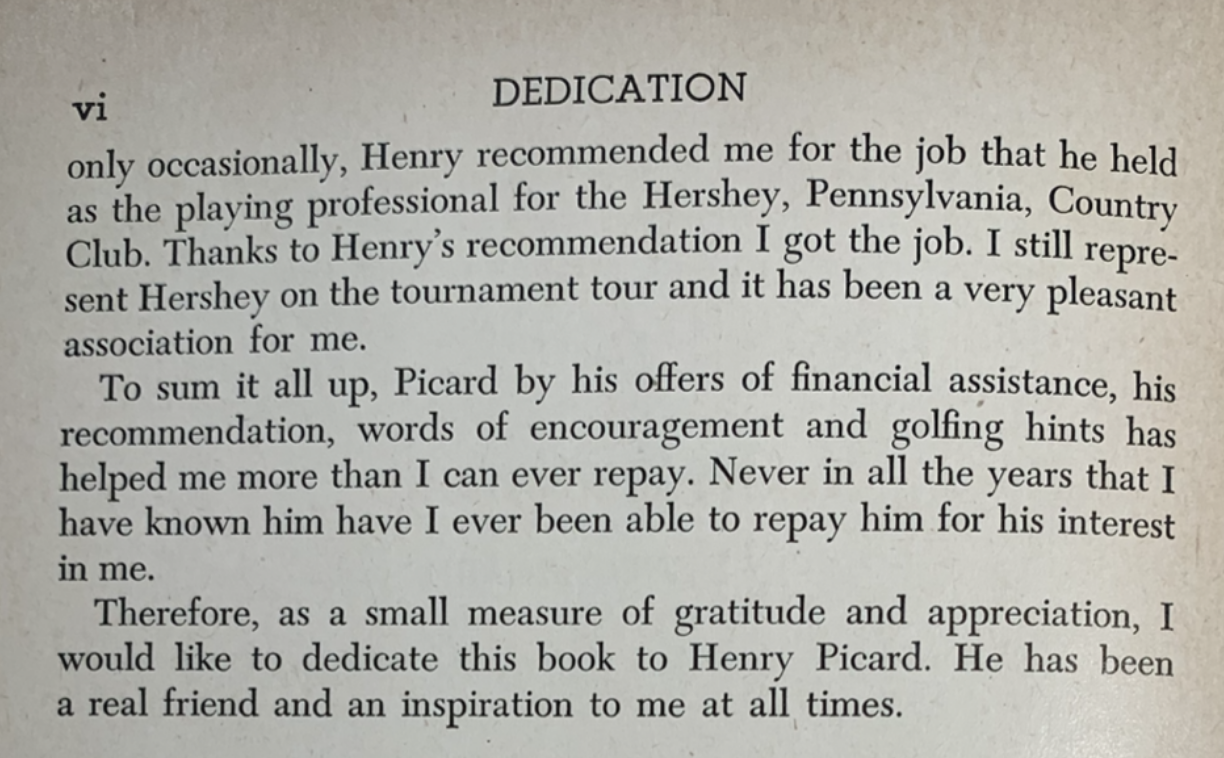

Pages 57 - May writes Hogan "thought so much of the [instruction] advice" given to him by Henry Picard in early 1940 that Hogan dedicated his first instruction book, Power Golf, to Pic. There are two problems with that claim. First, the dedication in Power Golf cites Picard's "encouragement and offer of financial assistance" that took place at the 1938 Oakland Open14 as the primary reason for Hogan's tribute, as the entire first page makes clear:15

Only in the penultimate paragraph does Hogan mention, in passing, Picard's "golfing hints":

Second, at the 1940 North-South where Picard's instruction was said to have paid off with Hogan's first individual win, Hogan never mentioned Picard or any instruction as a key to eliminating his troublesome hook: Hogan gave all credit to a driver given to him by Byron Nelson just before the tournament began.16

Biographer Curt Sampson recounts how, in later years, when Hogan was quizzed about Picard's help, Hogan had no memory of it,17 perhaps because it didn't happen the way Picard, or May, said it did.

Pge 60 - May writes about Hogan's playing accomplishments during the '40, '41 and '42 seasons:

[Hogan] led the tour in scoring average in 1940 and 1941.

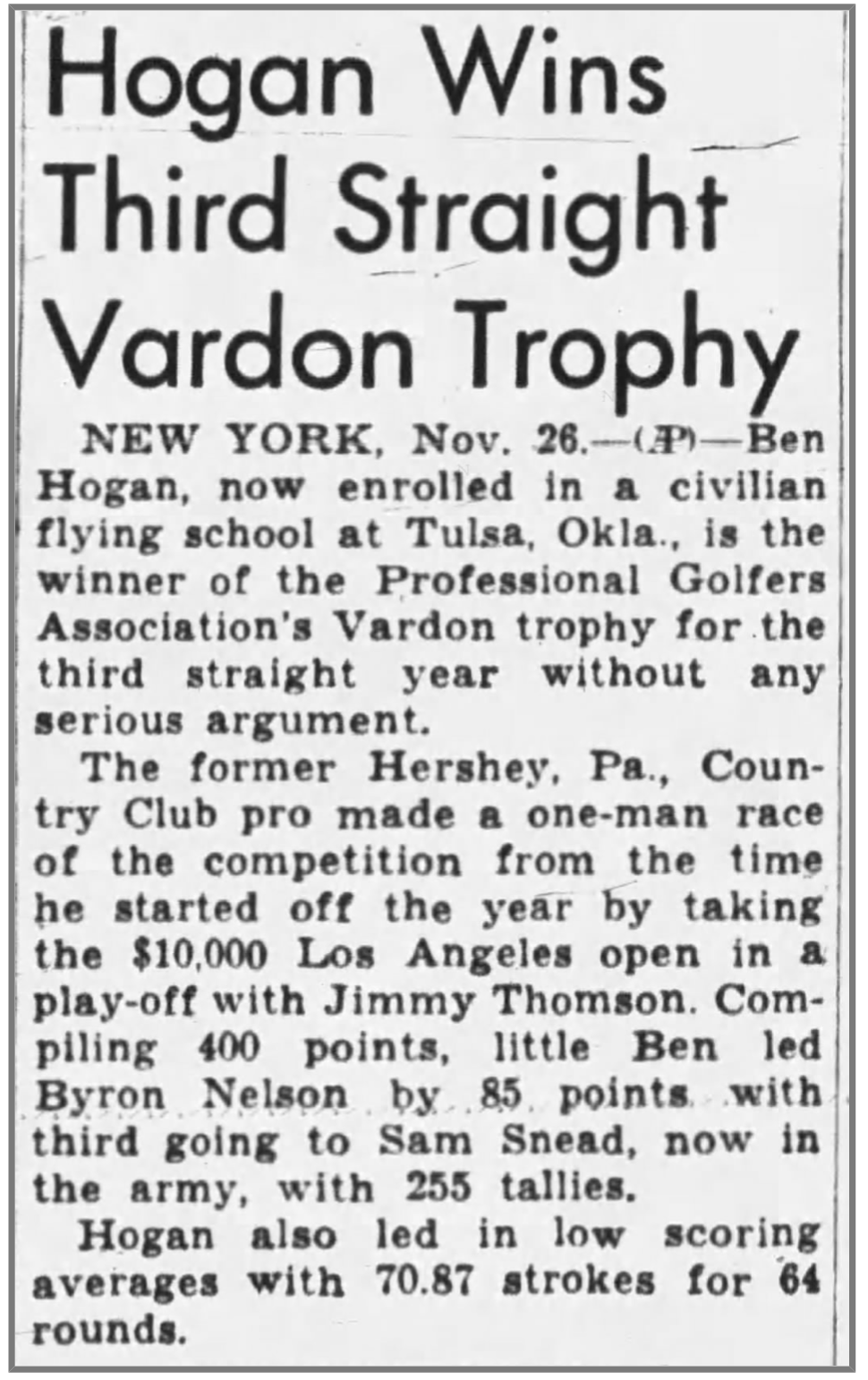

May omits, or is unaware, that Hogan also led the tour in scoring average in 1942. The PGA released the results in November, but subsequently decided to not award the Vardon Trophy.18 Page 60 - May writes:

Page 60 - May writes:

In those years [1940 through 1942], [Hogan] played in 72 tournaments and was in the top five in 57 of them. In 1941 alone, he played in 28 tournaments and finished in the top five in 26 of them.

May's figures are off by a bit. Overall, Hogan played 74 events during that period, including 29 in 1941. The top five tallies are correct.

Page 61 - May writes that "the people who mattered did not agree" that the Hale America was a major title. Nowhere does he say who the "people who mattered" are or where they voiced their disagreement. As documented in Myth Part 1, the event was widely covered as a major. May gives no evidence that there was ever an effort to strip away that status.

Page 63 - May writes that Hogan played 17 events in 1945, when in fact he played in 18.

Page 63 - May writes that Byron Nelson "won 19 times in 1945, including 11 straight." Nelson won 18 official events in 1945, plus the unofficial Spring Lake Pro Am which, if included, would extend his winning streak to 12.

Page 66 - May writes that labelling the Hale America as Hogan's "'first major' would be the source of debate for decades," yet provides nothing documenting the alleged debate. The historical record shows Hogan's "fifth Open" claim is the "source of debate."

Page 71 - May writes:

Demaret earned $385 for finishing third in Sacramento in 1935 and picked up another $750 with a third-place finish at Agua Caliente. Hogan played in some of these tournaments as well and didn't make a dime.

May makes several errors in the above. In 1935, Jimmy Demaret earned $250 for his tied-third-place finish at Sacramento, and $335 for his tied-fourth-place finish at Agua Caliente. As noted above, Hogan did not play any events in 1935. However, in 1932 he won $200 for a tied-15th-place finish at Agua Caliente, and in 1933 he withdrew from the event after 54 holes. Hogan would not play at Sacramento until 1938, when he won $350 for a third-place finish.

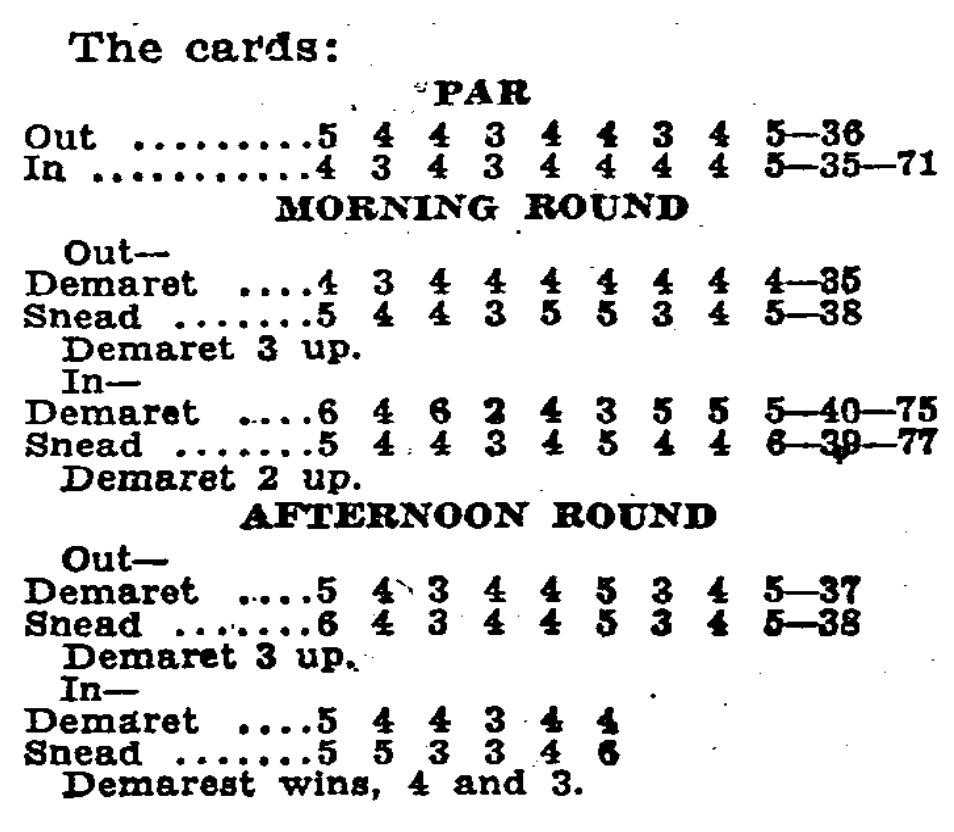

Page 72 - May writes about the final of the 1938 San Francisco Match Play, Jimmy Demaret's first tour win, where Jimmy defeated Sam Snead 4 and 3:

Snead never won a hole in the 15 that were played that day.

Both statements are wrong. The final was 36 holes, not 18, and 33 holes were played that day. Overall, Snead won seven holes: six during the morning 18, and one in the afternoon.19 Page 88 - May writes:

Page 88 - May writes:

The first several Masters were called the Augusta National Invitational Tournament. By 1938, Roberts had suggested calling the tournament that Masters, which Jones at first thought presumptuous.

In the press, the tournament was widely referred to as the "Masters" from its inception in 1934, which rapidly became its de facto name, although Jones insisted the official title be the "Augusta National Invitational." Jones eventually accepted reality and capitulated in 1939 when the "Masters Invitation Tournament" title was adopted. My podcast with Connor Lewis about the history of the Masters includes a discussion of those early years: TalkinGolf Episode 54

Page 94 - May writes:

When the final group finished, representatives from the three sponsoring organizations gathered with Hogan. George Blossom presented Hogan with the winner's gold medal, which had already been crafted in anticipation of an official US Open in 1942.

This photograph of the presentation ceremony shows that all three representatives presented the Hale America medal to Hogan, not just the USGA's Blossom. From left to right, Ed Dudley of the PGA, George Blossom of the USGA, Hogan and Tom McMahon of the CDGA: Page 104 - May writes:

Page 104 - May writes:

The late Dan Jenkins, who spent much of his golf writing career championing the Hale America as an official US Open, posed the question to the USGA Executive Secretary Joe Dey in the 1960s.

May gets Joe Dey's title wrong: in the 1960s, Dey was the USGA's Executive Director. In 1942, he was "Executive Secretary," the position Frank Hannigan described as "clerk-typist who spoke only when spoken to."

Page 105 - May writes:

It really wasn't until Arnold Palmer won the Masters and the US Open in 1960 that the modern Grand Slam came into focus. [Jeff] Martin and other golf historians generally credit Palmer's agent, Mark McCormack, and a Pittsburgh sportswriter named Bob Drum (who followed Palmer almost as much as O.B. Keeler followed Bobby Jones) with the concept.

May is incorrect, I do not credit McCormick or Drum with the "concept" of the "modern Grand Slam": the concept of the professional grand slam was in existence by the early 1930s, and was pursued, unsuccessfully, by several other players before Palmer. In my correspondence with Peter, this is what I wrote on the topic:

By the late 1930s, the consensus seemed to be there were at least two tiers of "majors": the top tier were "national championships," and included the two Opens, the PGA and the Masters; and the second tier included the Western Open and the North-South, that may have been even a notch below the Western. The Canadian Open was also occasionally included as a lower tier major.

In the 1950s, the pros considered George Mays' World Championship a "major," on the same level as the Western is my assessment. But, the big four were without question the two Opens, the PGA and the Masters.

In 1960, that group was dubbed the "Modern Grand Slam," in what I think was pretty much a marketing gimmick cooked up by Mark McCormick, and popularized by Arnie and Bob Drum.

My article detailing the genesis of the "modern Grand Slam" is here: Modern Grand Slam

Page 111 - May writes:

It was 10 years later, as Hogan was preparing for the 1952 US Open (which he would not win) that he mentioned to a sportswriter for Golf World magazine that he was really going after his fifth US Open championship.

In a classic "telephone game" jumbling of facts, May mistakes NEA Sports Editor Harry Grayson for a "sportswriter for Golf World magazine." May appears to have misread this passage from Tim Cronin's Reflections on Ridgemoor, a source Peter cites in the "Bibliography" (page 165):

Speaking to Harry Grayson, whom Golf World named the world's most enthusiastic newspaperman, Hogan said, "I'm really after my fifth Open."20

Page 114 - May writes:

So a golf clinic or a long-driving contest, while not regular staples of a tour event, were included in the Hale America package.

May is incorrect: clinics and long-driving contests were staples of PGA tour events in the 1940s.

Page 114 - May repeats the mistake he made on page 10:

The Masters field was about half the organizers originally expected.

Page 125 - May writes that heading into the 1946 US Open, Hogan had six victories; he actually had seven.

Page 152 - May writes concerning Hogan's prognosis following his auto-bus accident on February 2, 1949:

Hogan was told he might never walk again. He was told that he would, in all likelihood, never play golf again.

Historical accounts of what Hogan's doctors actually said on the record refute both claims. See: Never Walk Again

Page 153 - May makes a common misquote of Hogan's grim declaration after winning the 1951 US Open at Oakland Hills:

I'm glad I brought this course--this monster--to its knees.

Newspaper accounts from that day report Hogan said "to her knees."21

1. Associated Press, 88 To Receive Bids To Compete In 1942 Masters' Tournament, The Tampa Tribune, February 8, 1942, page 17.

2. Bob Considine, INS, On The Line, The Tribune, June 25, page 13.

3. Joe Williams, Demaret On Road To Victory In Hale America, But Goes to Pieces On 'Pressure Holes,' El Paso Herald-Post, June 22, 1942, page 8.

4. Associated Press, Sub-Par Rounds Mark Final Tune-Up For Masters' Tourney, Daily Press, April 9, 1942, page 9.

4. Charles Chamberlain, Associated Press, Hale America Group Asks for Snead and Turnesa, Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 2, 1942, page 14.

5. Charles Chamberlain, Associated Press, Hale America Scene Offers One of Sternest Tests in Country, Sioux City Journal, June 12, 1942, page 22.

6. James Dodson, Ben Hogan: An American Life, 2004, page 90.

7. Ben Hogan Interview with Ken Venturi, CBS Sports, May 12, 1983.

8. William D. Richardson, Lloyd Mangrum's Record-Breaking 64 Tops Field as Masters' Tourney Opens, The New York Times, April 5, 1940, page 27.

9. The Locker Room,

10. Kris Tschetter with Steve Eubanks, Mr. Hogan, The Man I Knew, 2010, pages 75 and 76.

11. James Dodson, Ben Hogan: An American Life, 2004, page 63. Gene Gregston, Hogan: The Man Who Played for Glory, 1990, page 29. Curt Sampson, Hogan - Updated Edition, 2001, page 24.

12. Byron Nelson, Third article of an instructive autobiographical series, The Piqua Daily Call, May 4, 1937, page 6.

13. Jimmy Demaret, My Partner, Ben Hogan, 1954, page 59.

14. Joan Flynn Dreyspool, Conversation Piece: Subject: Ben Hogan, Sports Illustrated, June 20, 1955, pages 37-39.

15. Ben Hogan, Power Golf, 1948, page v and vi.

16. Bill Boni, Blasts Out 66 With Driver Given To Him, The Daily Times, March 20, 1940, page 4.

17. Curt Sampson, Hogan - Updated Edition, 2001, page 68.

18. Associated Press, Hogan Wins Third Straight Vardon Trophy, The Tennessean, November 27, 1942, page 42.

19. Associated Press, Demaret Defeats Snead By 4 And 3, The New York Times, February 14, 1938, page 13.

20. Tim Cronin, Reflections on Ridgemoor, 2005, page 63.

21. Associated Press, Hogan's Biggest Kick From Open Was Beating Oakland Hills' Par, Richmond Times-Dispatch, June 17, 1951, page 65.